The Fine Art of Handwriting Is the Chief Form of Islamic Art

Standard arabic calligraphy:

Ancient craft,

modern art

The art of Arabic calligraphy has been enhanced and adult over the form of a millennia. It has written the word of God, helped preserve human knowledge and agreement, and borne witness to the devastation of Baghdad. It has been codified, stylized, and lent itself to abstraction. It has even struggled with the modern world and found renewed life in both fine art and typography.

Nowhere is calligraphy more than revered than in Islam. Co-ordinate to Islamic tradition, God "taught with the pen, taught man that which he knew non" (Qur'an 96:iv). No wonder the art of writing is both admired and cherished every bit a visual expression of faith.

Now it is beingness celebrated in all its forms, with Saudi Arabia extending the Year of Arabic Calligraphy into 2021 and UNESCO registering the art class on its Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Arabic calligraphy is taking its rightful place at the eye of Arab identity. As the Iraqi calligrapher Wissam Shawkat says: "This is the one affair that is pure for us."

Tracing origins

On the banks of the Euphrates river, roughly 170 kilometers s of Baghdad, lies the Iraqi urban center of Kufa. One time renowned as a center of learning during the Islamic Golden Age, information technology has at present been all only consumed past Najaf.

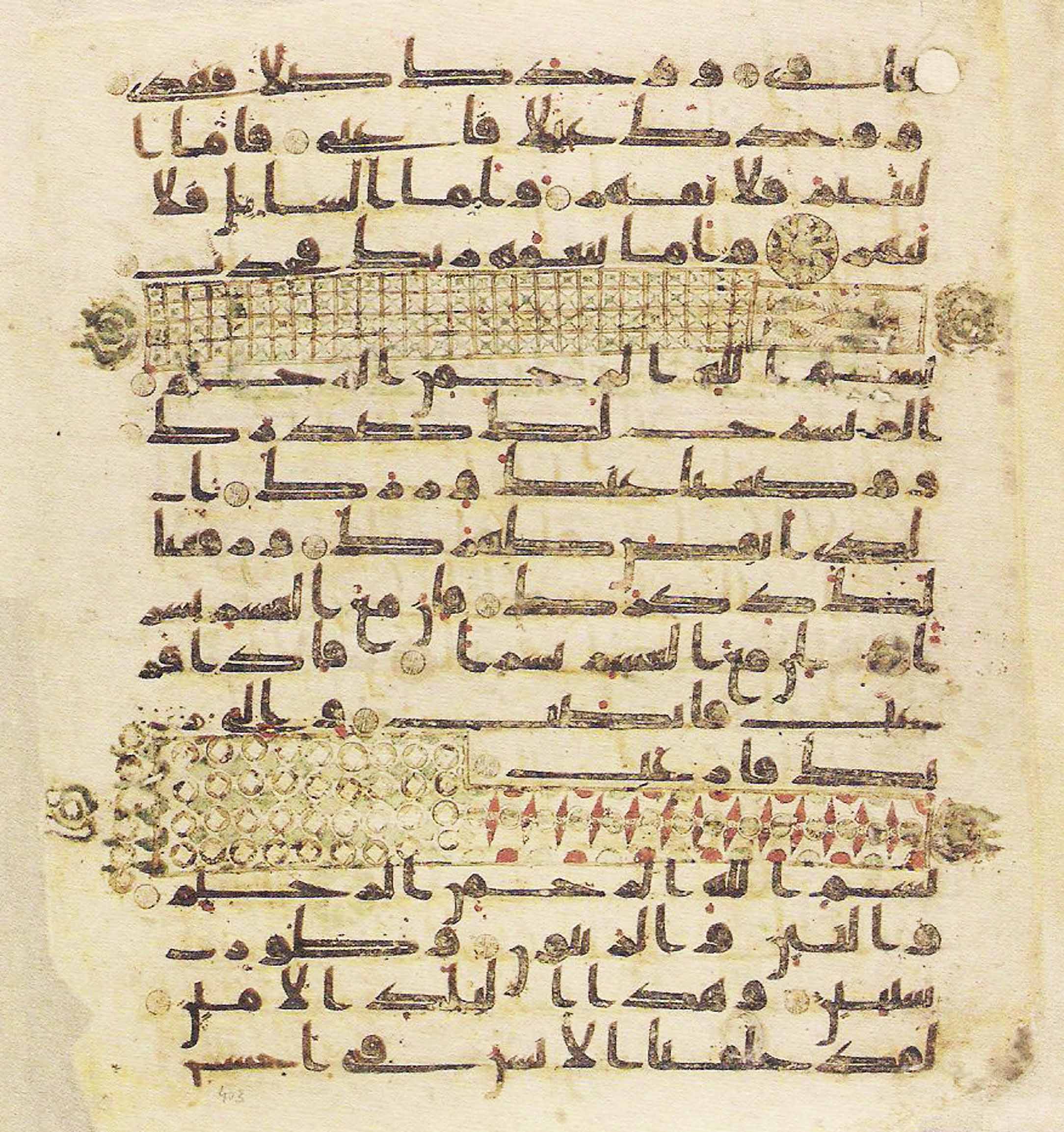

Kufa is the metropolis that gave its proper name to Kufic, the earliest example of a universal calligraphic style and a favored script for transcription of the Holy Qur'an. Many of the earliest extant copies of the Islamic holy book, including the Blue Qur'an — a 9th-century manuscript believed to have been produced in Espana — and the Topkapi manuscript, the oldest near-complete Qur'an in existence, were written using this foundational script.

The Blue Qur'an — a ninth-century manuscript believed to have been produced in Spain — was written in Kufic script. (Getty Images)

The Blue Qur'an — a 9th-century manuscript believed to have been produced in Spain — was written in Kufic script. (Getty Images)

Kufic'south geometric elegance also meant it was well suited to architectural ornamentation, with one of its earliest known examples institute in a 240-meter-long Qur'anic inscription inside Jerusalem's Dome of the Rock. The oldest, however, dates from 644 CE and is engraved on a stone nigh AlUla in Kingdom of saudi arabia, according to the Kingdom'south submission to UNESCO's Memory of the Earth annals. Known as The Inscription of Zuhayr, it is situated on an ancient trade and pilgrimage route between Al-Mabiyat and Madain Saleh and states the date of death of Umar Ibn Al-Khattab, the 2nd Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate.

However, the exact origins of Kufic and the scripts that preceded information technology are unclear. The Standard arabic alphabet is believed to take evolved from Nabataean, an Aramaic dialect used by a semi-nomadic Arab people who inhabited northern Arabia, the southern Levant and the Sinai Peninsula from around the fourth century BCE. Today, the Nabataeans are best known for the architectural wonders they bequeathed the earth, including Petra in Hashemite kingdom of jordan and Madain Saleh in Saudi Arabia. What is less appreciated is their pivotal function in the formation of the Arabic script.

A Nabataean inscription in AlUla in Saudi arabia. The Standard arabic alphabet is believed to have evolved from this Aramaic dialect. (Getty Images)

A Nabataean inscription in AlUla in Saudi arabia. The Arabic alphabet is believed to have evolved from this Aramaic dialect. (Getty Images)

The Nabateans used a form of writing that flowed from right to left and had strong similarities with Arabic, including its cursive nature and its reliance on bodies of text that consisted largely of consonants and long vowels. How Nabataean evolved into Arabic is not precisely clear, simply in 2014 a articulation Saudi-French archaeological team discovered what is, at nowadays, the oldest known inscription in the Arabic alphabet. Dating from 469 to 470 CE, information technology was establish 100 kilometers due north of Najran in Saudi Arabia and is written in a mixed text known every bit Nabataean Arabic. The discovery, described at the time as the 'missing link' betwixt Nabataean and Arabic writing, helps explain why Nabataean is considered the directly forerunner to the Arabic script. Prior to this, the earliest extant Standard arabic inscription was from Namara in mod mean solar day Syrian arab republic (dating from 328 CE), merely it is written solely in Nabataean characters.

The earliest course of Arabic script is known as Jazm, which in plough adult into a number of differing styles, including Hiri, Anbari, Makki and Madani. These styles were named subsequently the cities or regions from which they emerged (for example, Makki and Madani were from Makkah and Madinah respectively) and were particular to their time and location. Madani and Makki are also linked together under Hijazi, the commonage name for a number of scripts from the Hijaz region. Ma'il, some other Hijazi script used in a number of the earliest Qur'anic manuscripts, is believed to be the straight predecessor of Kufic. The so-chosen "Birmingham Qur'an," from the 7th century CE, is a wonderful, albeit incomplete, case of the Hijazi style.

A composite epitome featuring examples of Madani script, which was adult in Madinah from the primeval form of Arabic script known every bit Jazm. (SPA)

A blended image featuring examples of Madani script, which was developed in Madinah from the earliest form of Arabic script known equally Jazm. (SPA)

Why Kufic emerged as a dominant calligraphic style during the seventh century is open to debate, simply its significance lies in the preservation of the Qur'an, the Islamic conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries, and its geometric beauty. Every bit both Islam and the Standard arabic language spread across Northward Africa and into the Iberian Peninsula, so the importance of the Arabic script intensified, with the need for an authoritative script that could combine aesthetics with readability. Over time, variations of Kufic would emerge, with Eastern Kufic (created by the Persians), the Maghrebi script (developed in North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula), and plaited and square Kufic epitomizing the evolution of a calligraphic style.

"The Kufic script is considered very important and all the same relevant today considering it was the first script to be used to write the Holy Qur'an," Saudi calligrapher Nasser Al-Salem explains.

"Kufic is a fascinating calligraphic style because it's so varied and rich," adds Bahia Shehab, an artist, historian and professor of design at the American University in Cairo (AUC). "You lot take the uncomplicated square Kufic, y'all have the early Kufic of the early Qur'ans, you have the Kufic from the East, the Kufic from the Due west, you have the floriated Kufic, the foliated Kufic, the knotted Kufic. You might remember it'due south only one style of script, just information technology'due south so rich and varied and I dearest the geometry of it — the construction of it."

This bowl from around 900 CE hails from present-day Iran and features an case of knotted Kufic script. (Alamy)

This basin from effectually 900 CE hails from nowadays-twenty-four hours Iran and features an instance of knotted Kufic script. (Alamy)

Early on versions of Kufic did non include the dotting that later distinguished letters from one another, nor did they have any signs to display the correct pronunciation of words. A right interpretation of the text would depend on the skill of the reader, who was assumed to have the knowledge to decipher words that were left with unmarked vowels and without consonant points. This did not modify until Abu Al-Aswad Al-Du'ali, considered the male parent of Arabic grammar, invented a system of consonant differentiation called i'jam and vowel indication (tashkeel) in the second half of the 7th century.

That system was further adult in the eighth century past the philologist and grammarian Al-Khalil Ibn Ahmad Al-Farahidi, who wrote the first Standard arabic dictionary and introduced a organisation of curt vowel marks known as harakat. Both Al-Du'ali and Al-Farahidi lived and worked in Basra, Iraq.

Writing cursive is much faster than writing geometric script, and if you want to grow an empire, you want to spread your bulletin and you desire to write more books.

Although Kufic would remain in use until the 12th century, its popularity waned, primarily because of the emergence of more legible cursive scripts such every bit Toumar, Muhaqqaq and, in particular, Naskh, which was easier and faster to write and would go along to become the preferred script for books and administrative documents within the Abbasid Caliphate.

"There are many theories almost why Kufic went out of apply, merely the most logical i I've read and then far is speed," says Shehab. "Writing cursive is much faster than writing geometric script, and if you want to grow an empire, you want to spread your bulletin and you want to write more books. And writing with a cursive script is faster than writing with a more angular geometric script that needs more precision and time.

"Simply Kufic never fully disappeared. It has always had revivals. For example, during the Mamluk period, Kufic started reappearing on Ayah headings in the Qur'an and in the famous Sultan Hassan Mosque. There's an elegance in its geometry and Kufic will forever be used, although we nonetheless need to discover what its undercover is."

Written in Kufic script, the Topkapi manuscript is the oldest most-complete Qur'an in existence and dates from the eighth century. (Alamy)

Written in Kufic script, the Topkapi manuscript is the oldest virtually-complete Qur'an in existence and dates from the 8th century. (Alamy)

The Islamic conquests of the 7th and eighth centuries intensified the need for a script that could combine aesthetics with readability. Depicted here is the Umayyad Caliphate's conquest of the Christian Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania in 711. (Getty Images)

The Islamic conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries intensified the need for a script that could combine aesthetics with readability. Depicted here is the Umayyad Caliphate's conquest of the Christian Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania in 711. (Getty Images)

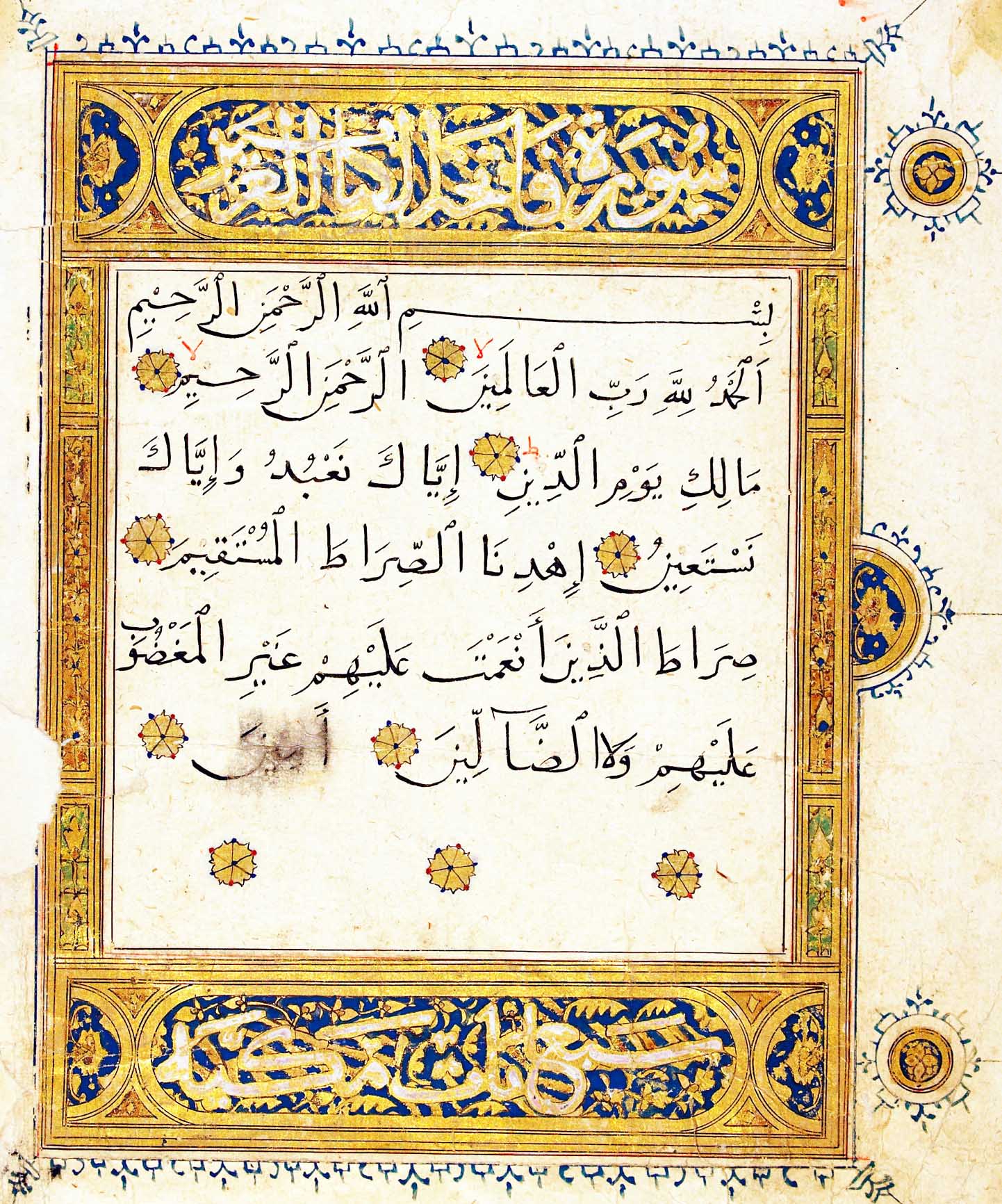

Although Kufic would remain in utilise until the 12th century, its popularity waned, primarily because of the emergence of more than legible cursive scripts such equally Naskh, pictured here. (Alamy)

Although Kufic would remain in utilize until the 12th century, its popularity waned, primarily considering of the emergence of more legible cursive scripts such as Naskh, pictured here. (Alamy)

Codifying calligraphy

Although largely divers by its angularity and geometric qualities, there were no rules attached to the use of Kufic, nor was there any form of universally accepted standardization. This led to widely differing versions of the script. This lack of standardization would come to an end (for cursive scripts at to the lowest degree) with the arrival of Abu Ali Muhammad Ibn Ali Ibn Muqla — meliorate known simply as Ibn Muqla — a primary calligrapher and vizier within the Abbasid Caliphate, and the kickoff person to codify the principles of calligraphy.

Ibn Muqla's organization of proportional scripts (chosen Al-Khatt Al-Mansub) would mark the birth of visual consistency within the Arabic writing organisation. Reflecting an association with the divine, the system he developed ensured the letters of any given script were in proportion with one another. This was achieved past establishing the rhomboid dot (created by the nib of a calligrapher'south qalam), the length of the aleph (the first letter of the Arabic alphabet), and the circle (with a diameter equal to the height of the aleph) as the units of measurement past which the size of all letters is calculated. This codified organization was applied to 6 calligraphic scripts known as Al-Aqlam Al-Sitta: Naskh, Muhaqqaq, Rayhani, Thuluth, Riqa (not to be dislocated with Ruqʿah) and Tawqi. For example, the height of the aleph measures eight dots in Muhaqqaq, seven in Thuluth and vi in Tawqi. "You can call Ibn Muqla the engineer of writing," Al-Salem says of the celebrated calligrapher. "He nerveless all of this data regarding the techniques of writing. He was the i putting all of this information in one place so that it could be passed on from 1 generation to another."

Not a single line of Ibn Muqla's work has survived, only his touch on calligraphy was profound.

Non a single line of Ibn Muqla'due south work has survived, but his bear on on calligraphy was profound. He brought mathematical accuracy to the reproduction of messages and heightened the aesthetics of calligraphy through geometric design. However, the violent nature of his demise — his right paw was cutting off and then he could not write, and when he protested with words, his tongue was cutting out too — has left an emotional scar. He eventually died in prison house in 940 CE.

"What is deep about the legacy of Ibn Muqla is his tragic life, and it affects us all emotionally as calligraphers," says the Iraqi artist and calligrapher Hassan Massoudy. "Even if we have not seen his work, everyone acknowledges that he delineated and reinforced simplified geometrical rules for the shape of letters. He is the only well-known figure up until the tenth century. Amidst numerous other calligraphers, he remained the most famous. This gives me hope in terms of the respect that society gave calligraphers. Only nosotros are also shocked past the savagery with which he was treated in Abbasid society because he said they had reached such levels of decadence and luxury that they no longer deserved the Kufic script, and ought to be given a softer calligraphic style."

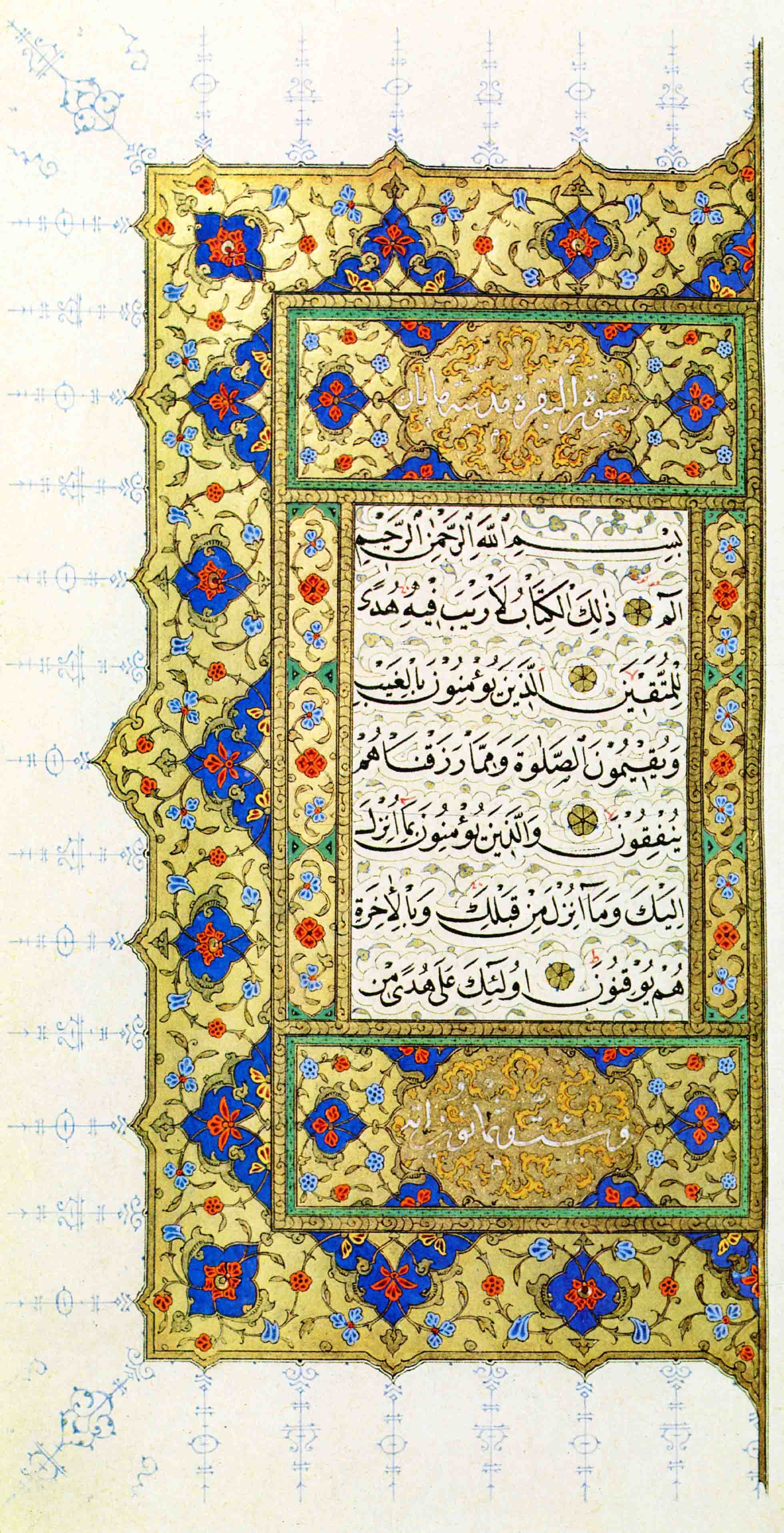

In the years and centuries post-obit Ibn Muqla'due south expiry his piece of work was refined by Ibn Al-Bawwab and Yaqut Al-Musta'simi, both of whom spent the majority of their lives in Baghdad. The old produced an estimated 64 copies of the Qur'an, the near famous of which — and the only i still in existence — is at present in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin. Information technology is 1 of the earliest known Qur'ans to take been produced on paper rather than parchment, and one of the primeval to have been written in the Naskh script.

Ibn Al-Bawwab produced an estimated 64 copies of the Qur'an. This i, written in Naskh script, is housed at the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin. (Chester Beatty Library)

Ibn Al-Bawwab produced an estimated 64 copies of the Qur'an. This ane, written in Naskh script, is housed at the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin. (Chester Beatty Library)

Information technology was Ibn Al-Bawwab who took Ibn Muqla's system of proportional scripts and artistically elevated them through the graceful use of rhythm and movement. "Despite the regularity of the letters, in that location is nothing dryly mechanical well-nigh them and that, surely, was the essence of Ibn Al-Bawwab'southward stimulating contribution to the fine art of calligraphy," wrote David Storm Rice in 1955. "He achieved a gracefully flowing script while preserving a systematized and proportioned alphabet. It looks easy to imitate and yet defied imitation."

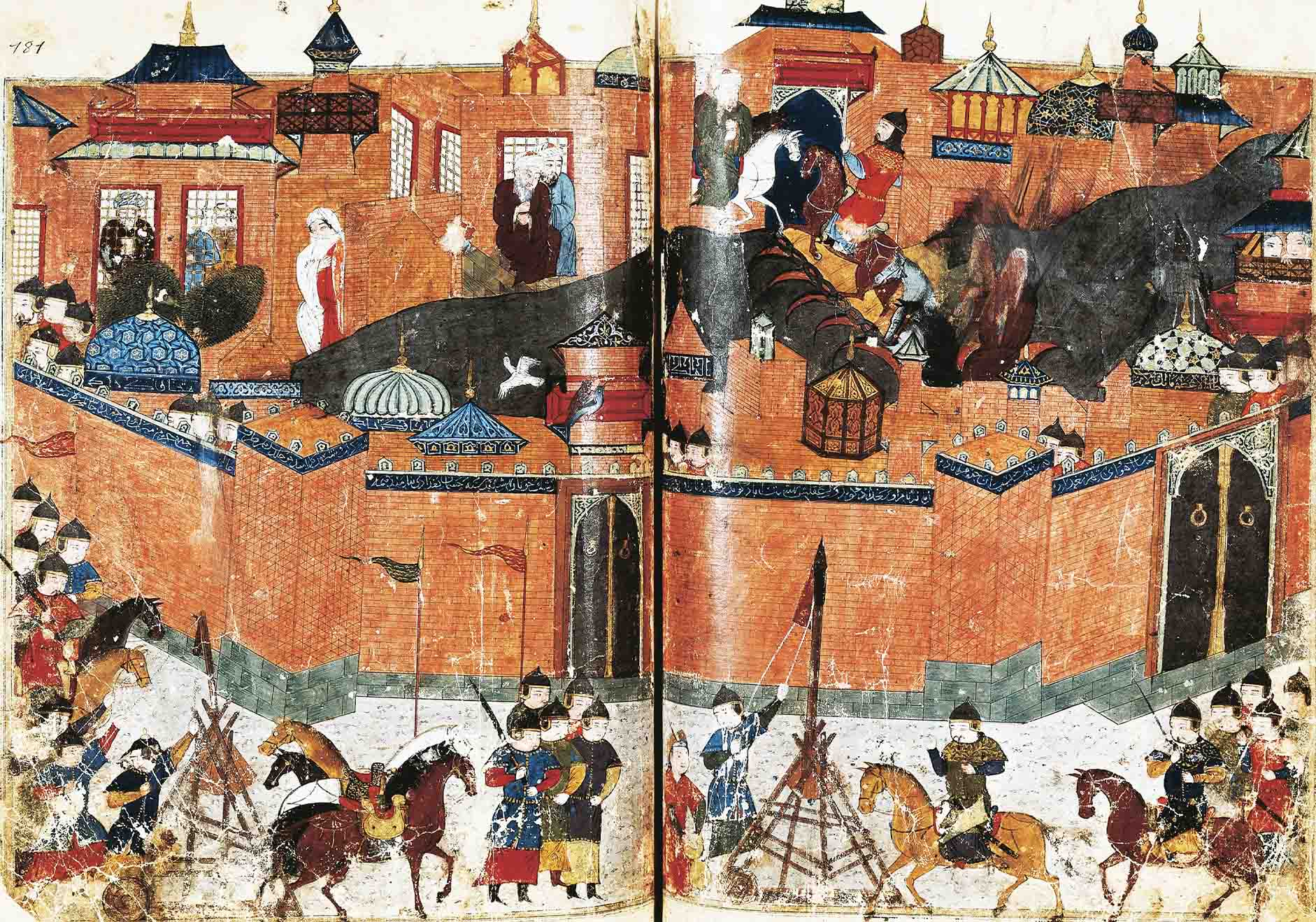

Al-Musta'simi, the concluding of the not bad medieval calligraphers, would farther refine the Al-Aqlam Al-Sitta during the 13th century. Known as Sultan Al-Kuttab (Sultan of Calligraphers), he served as secretarial assistant to the terminal Abbasid caliph and survived the sacking of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258. He replaced the directly-cut qalam (the calligrapher's pen) with an oblique cutting, resulting in a more refined and elegant script. Significantly, it was Al-Musta'simi who would human activity every bit the inspiration for calligraphers following the destruction of Baghdad and the encarmine terminate of the Islamic Golden Historic period.

In the aftermath of the Mongols' sacking of the Abbasid capital, the heart of calligraphic excellence would somewhen shift north to Istanbul. The Ottomans invented or perfected several styles, including Ruqʿah, with its straight lines and simple curves, and the intricate, heavily stylized Diwani script, developed for employ in court documents to ensure confidentiality and prevent forgery.

A 19th-century instance of the intricate, heavily stylized Diwani script past Mehmet Izzet Al-Karkuki is shown hither. (Alamy)

A 19th-century example of the intricate, heavily stylized Diwani script by Mehmet Izzet Al-Karkuki is shown here. (Alamy)

"It was said in the by that handwriting is emblematic of humanity itself, and when nosotros come across lines from the past, we can likewise see the nature of the calligrapher clearly in their writings," says Massoudy. "For example, in the 15th- and 16th-century Ottoman state there were two great calligraphers whose work has reached us in the present mean solar day. The offset is Sheikh Hamdullah, whose calligraphy was full of fragile and sugariness feelings. The other is Ahmed Karahisari, who congenital complex letters, especially the letter 'A' (the aleph), which he drew alpine like a lighthouse. A calligrapher therefore reveals himself by creating a closed, static and rigid slice of piece of work, simply another calligrapher can requite the same letters new vigor, openness and vitality."

Hamdullah was foremost amongst Turkish calligraphers and is considered the father of the Ottoman schoolhouse. Inspired by the work of Al-Musta'simi, he refined the six standard scripts first codified by Ibn Muqla, perfected the Naskh and Thuluth scripts, and produced an estimated 47 copies of the Qur'an. His use of Naskh in particular turned that script into the nearly elegant and legible of all for transcription of the Qur'an.

An undated example of Thuluth script. (Sharjah Museums Authority)

An undated example of Thuluth script. (Sharjah Museums Authority)

Also developed during this period was the Jali — or large — style of Thuluth and Diwani, an incredibly intricate style which tin claiming even experienced calligraphers. "It has very distinctive characteristics and the more than you study it, the more you discover," says the Saudi-Iraqi artist and designer Majid Alyousef. "It reminds me of fractal drawings where you run into more details appearing every time y'all zoom in. This feature fabricated it more interesting to report and investigate, especially when I started studying design and abstraction."

Advisedly studying and investigating the fine art of calligraphy is important to artist Majid Alyousef, whose love of the written word began with a case of bad handwriting.

Significantly, the Ottomans categorized scripts by usage and created a system that determined which scripts would be used for certain functions based on their form. This meant that each script's size, complexity and fifty-fifty harmonic proportions would decide their use. For example, the Tumar script was used for covenants, Ruqʿah was reserved for simple handwriting and correspondence, and Diwani Jali was utilized for formal brusk pieces such equally invitations, certificates and religious quotations.

Ruqʿah was mainly reserved for uncomplicated handwriting and correspondence. (Sharjah Museums Authority)

Ruqʿah was mainly reserved for simple handwriting and correspondence. (Sharjah Museums Authority)

In the aftermath of the Mongols' sacking of Baghdad in 1258, depicted here, the center of calligraphic excellence would somewhen shift north. (Getty Images)

In the aftermath of the Mongols' sacking of Baghdad in 1258, depicted here, the centre of calligraphic excellence would eventually shift north. (Getty Images)

Sheikh Hamdullah, who worked between the 15th and 16th centuries, produced an estimated 47 copies of the Qur'an. (Alamy)

Sheikh Hamdullah, who worked between the 15th and 16th centuries, produced an estimated 47 copies of the Qur'an. (Alamy)

Calligraphy's many uses

Although the development of Arabic calligraphy is strongly tied to the Qur'an, from the outset it was used for a diverseness of functions. Information technology has adorned almost every surface, has been embraced by a multitude of professions, and has been employed in innovative ways to create works of art based on private letters or words. As such, it is an intrinsic part of both Arab and Islamic fine art.

Its most obvious manifestation — and the one nosotros have been mostly concerned with and then far — has been the written word on either parchment or paper. Yet even this had multiple uses and was in no mode limited to Islamic texts. "Aboriginal bibles were also transcribed in Arabic script," notes Lana Shamma, Art Jameel's senior manager of public programs. "As a whole, this reverence for the written discussion too translated to a reverence for the Standard arabic linguistic communication, which remains live in present-24-hour interval culture."

The Ottomans may have categorized scripts by grade and role, but the use of any given script was always adamant by its audience, its artistic form, and the content of the writing itself. Naskh, for instance, was a preferred script for manuscripts and administrative documents; Rayhani was used for chancellery letters and edicts; and the highly secretive Diwani was, equally mentioned, used for court correspondence. In Persia, the Nastaliq script, which emerged during the 14th and 15th centuries, became the preferred manner for poetic texts.

This collection of Persian prose is written is Nastaliq script and hails from circa 1475-1500. (Getty Images)

This collection of Persian prose is written is Nastaliq script and hails from circa 1475-1500. (Getty Images)

As with many forms of expression, all the same, the Standard arabic script also "lends itself to abstraction and to the breaking of 'rules' to create distinct styles," says Shamma. "Its flexibility likewise makes it appealing for applications on multiple media, ranging from architecture to book illumination to embroidery on textiles." As such, Arabic calligraphy tin can exist found on everything from ceramics, textiles and enameled glass to coins, metalwork, carpets and woodcarvings.

Styles of floriated Kufic were adult to adorn ceramics in the Fatimid era; inscribed textiles known every bit tiraz were embroidered with the names of Caliphs and bestowed as gifts; and mirrors cast in statuary were engraved with expert wishes. Calligraphers would often create works of exquisite beauty and sometimes staggering complexity, exploiting Arabic's versatility and its potential as an ornamental form.

This twelfth-century mirror bandage in bronze features foliated Kufic good wishes on the outer rim. (Alamy)

This 12th-century mirror cast in bronze features foliated Kufic good wishes on the outer rim. (Alamy)

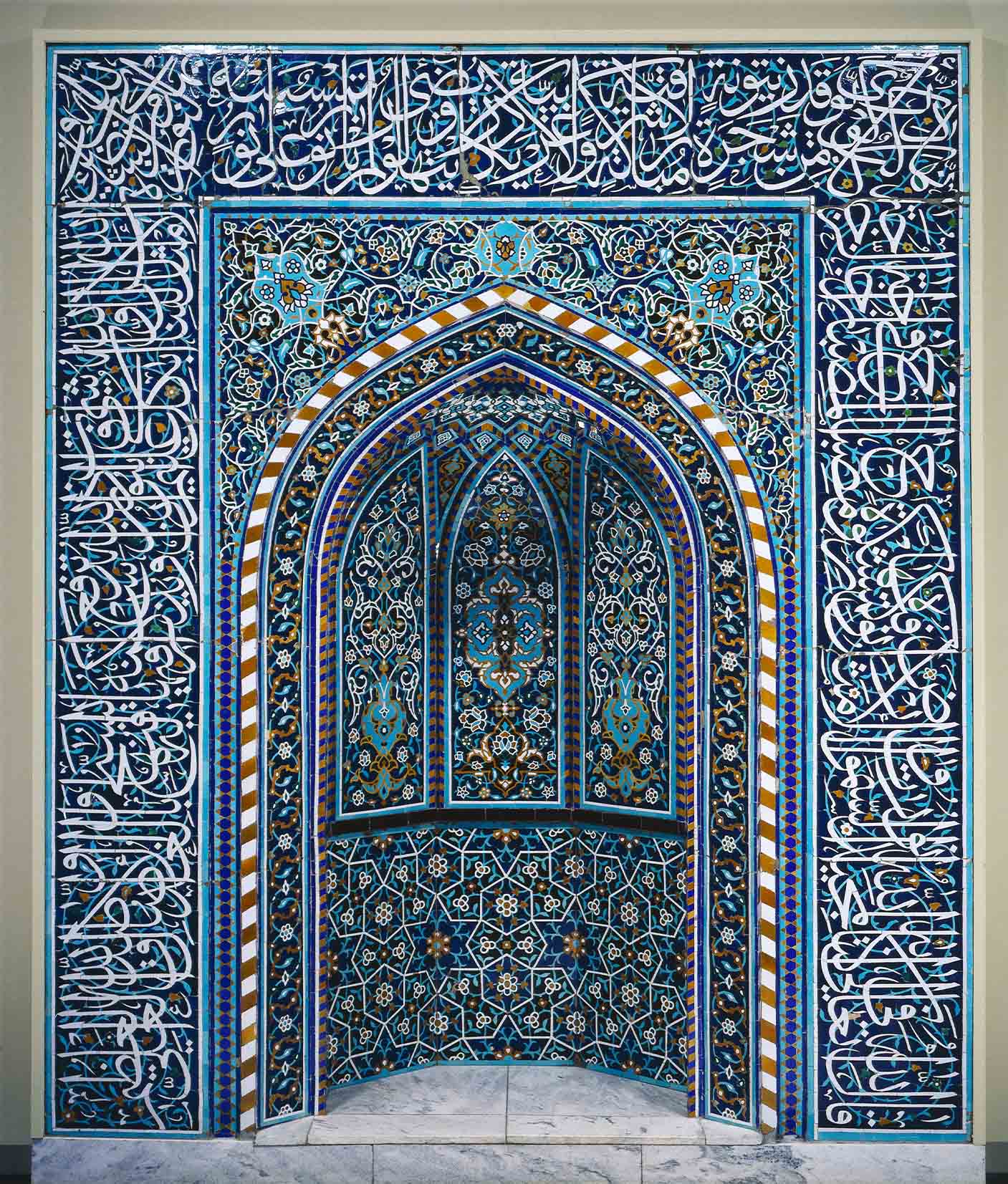

Certain scripts — particularly Kufic and Thuluth — also lent themselves to compages. Calligraphic inscriptions adorn a diverseness of religious, military and borough buildings and, in many cases, were monumental in stature. Equally mentioned previously, one of the earliest known examples of architectural inscription can be found in Jerusalem's Dome of the Stone, but inscriptions are prevalent within buildings across the Islamic globe. They beautify the Sultan Hassan Mosque in Cairo, one of the finest examples of early Mamluk compages; the Bou Inania Madrasa in Meknes, Morocco; and the Shah Mosque in Isfahan, considered a masterpiece of Farsi architecture.

Calligraphy adorns the Sultan Hassan Mosque in Cairo, one of the finest examples of early on Mamluk architecture. (Shutterstock)

Calligraphy adorns the Sultan Hassan Mosque in Cairo, 1 of the finest examples of early Mamluk compages. (Shutterstock)

AUC's Shehab believes calligraphy had iii main architectural roles: "The outset one was informative, considering buildings normally stated who the patron was, when the building was constructed, and the name of the building. If at that place was a waqf (a charitable endowment) for the edifice it was also either engraved or painted inside the building.

"The second one was decorative. Because zoomorphic and human representations were not accepted in religious spaces, calligraphy and geometric motifs, which we call Arabesque, were cardinal to decorating internal spaces," she continues.

"And I think the third idea is a manifestation of ability. When you have these large, beautiful scribed paintings in a mosque in Turkey, or on a facade in Mamluk Egypt, or on a Safavid edifice in Iran or in Mughal India, this beautiful calligraphy is a manifestation of piety just also of power — of respect for God. Because when you stand up in front of something and so beautiful y'all are in awe."

This beautiful calligraphy is a manifestation of piety but also of power — of respect for God.

In the Bibi-Khanym Mosque in Samarkand and the Mausoleum of Qalawun in Cairo, it is the bricks and tiles that form the text using geometric Foursquare Kufic. Referred to every bit Banna'i in Farsi, this style of decorative brickwork may accept originated in Syrian arab republic and Iraq simply arguably found its greatest expression in Iran and Central Asia. In the Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi in Kazakhstan, for example, blue brickwork spells out the names of Allah and of the Prophet Muhammad, while raised brickwork in both Kufic and Naskh can be found on the Minaret of Saveh in Islamic republic of iran.

Calligraphers were as well at the heart of the age of discovery encouraged by the Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad. Astronomers, physicians, mathematicians and cartographers may have expanded Arab and Muslim knowledge, acting every bit a span of learning between Aboriginal Hellenic republic and the European Renaissance, simply it was calligraphers who helped record that knowledge. Calligraphers such as the 10th-century bibliographer Ibn Al-Nadim, whose "Kitab Al-Fihrist" is an index of all the books written in Arabic at the time of its publication. Hence calligraphers played a office in "preserving human being knowledge and history," says Alyousef, only every bit calligraphy itself acted every bit a "symbol of uniqueness and a signature of identity." Something that it continues to do today.

Bated from paper and parchment, Arabic calligraphy can exist found on ceramics, pictured here, textiles, metalwork, carpets and more. (Shutterstock)

Aside from paper and parchment, Arabic calligraphy can be establish on ceramics, pictured hither, textiles, metalwork, carpets and more than. (Shutterstock)

A close up of the calligraphy-adorned walls in the Bou Inania Madrasa in Meknes, Morocco. (Shutterstock)

A shut up of the calligraphy-adorned walls in the Bou Inania Madrasa in Meknes, Morocco. (Shutterstock)

In the Bibi-Khanym Mosque in Samarkand, it is the bricks and tiles that class the text using geometric Kufic. (Shutterstock)

In the Bibi-Khanym Mosque in Samarkand, it is the bricks and tiles that form the text using geometric Kufic. (Shutterstock)

A calligrapher'southward

toolkit

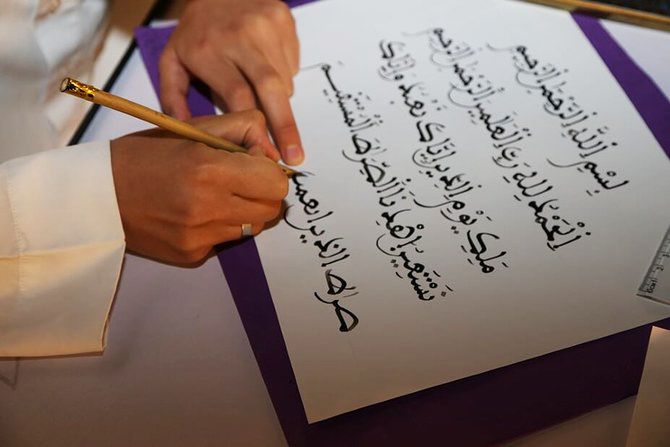

"I've been doing calligraphy for 35 years and I'm still practicing," says Shawkat. "I exercise daily. It'southward similar music. The more y'all practice, the more your letters mature."

Artist Wissam Shawkat explains why he believes artists should constantly innovate.

Equally with all forms of art, calligraphy is as much about patience, practice and passion equally it is about inherent skill. That means years spent with pen, ink and paper, mastering an fine art form that is cherished for its dazzler, clarity and harmony. Traditionally, that would have meant being taught by a master calligrapher, who would have set at least i day aside each week to correct students' calligraphic studies. This tradition continues today, although the early 20th century saw the establishment of calligraphy schools including the Madrasat Tahsin Al-Khotoout, the Khalil Agha School in Cairo, the Medresetul Hattatin in Istanbul and the Dar Al-Qalam Circuitous in Madinah.

We visit the Dar Al-Qalam Complex in Madinah to detect out more than about how students are embracing the fine art of calligraphy.

One former attendee of the Madrasat Tahsin Al-Khotoout was Massoudy, who spent a short period of time there in 1980. "The encounters between great calligraphers and amateurs fabricated my time at that place feel longer than information technology was," he recalls. "I had a like feeling when I went to the capital of Ottoman calligraphy, Istanbul. I met the last great Ottoman calligraphers, such as Hamid Aytaç, who created calligraphy for me that I cherish. Despite spending less than a month on that trip, it felt as if I had been studying and learning in that location for many years. Truth be told, I had hundreds of questions that I had not establish answers for. And my trip to Turkey gave me the answers to most of them."

For most modern calligraphers their first introduction to the fine art of calligraphy was at primary schoolhouse. Information technology was at that place that the Lebanese artist and poet Samir Sayegh offset used 'forbidden' ink and was praised for the beauty of his handwriting. It was at school in Najaf that Massoudy, besides, was applauded for his calligraphy, before moving to Baghdad as an amateur and spending his days "practicing from morning until night."

"Sometimes I'd have a coming together or encounter that broadened time," he remembers. "An 60 minutes with the calligrapher Hashem Al-Baghdadi (considered the last of the classical calligraphers) felt like a full yr to me. On a day when he would draw words for me I would feel that I had grown bigger."

Al-Salem describes the rigorous training and dedication information technology takes to even brainstorm to master the art class: "I studied calligraphy most the Holy Mosque in Makkah. I had a calligraphy mentor and teacher and I studied during summer holiday and three times a week… I would get after Fajr prayer and spend all day at that place studying and learning — I was xiii years one-time," he says.

He, like the majority of calligraphers, relies on essential tools that have non inverse much throughout history — the reed pen (qalam), a choice of knives (for cutting the reed or bamboo), various inks (traditionally fabricated of soot dissolved in water and Standard arabic gum), and the parchment or paper on which to write.

Reed pens were called because they combined hardness and softness, solidity and flexibility, and allowed for an easy catamenia of ink to the surface of the paper. Various accessories, such as pen boxes and inkwells, would adorn a calligrapher's desk, while calligraphy carried out on other materials, such every bit metal or wood, would require a option of carving tools.

In traditional calligraphy books, tens of pages describe the reed pen and the manner in which it is cutting, slit, dried and preserved.

"In traditional calligraphy books, tens of pages describe the reed pen and the style in which it is cut, slit, dried and preserved," says Sayegh, whose Beirut studio is filled with inkwells, pliers, end cutters, a hacksaw, 2 wooden mallets and an old hand-operated drill. "Tens of pages, likewise, describe the pocketknife that the calligrapher should utilize in making the reed. Many other pages draw inks and how to produce and prepare them."

In the "Subh Al-A'sha," an encyclopedia written by the Egyptian polymath Al-Qalqashandi in the early years of the 15th century, in that location are hundreds of pages on pens, knives, inks and other technical issues that the calligrapher needs to practise in gild to master the fine art of calligraphy. The pecker of the reed pen, for case, should be cut at an inclined bending and and then slit in the heart to facilitate the menstruation of ink. The angle of the inclined cut depends on the intended script, while the type of reed used is largely down to personal preference.

"Cut the pen at an inclined angle brings together both sides of the pen, thus helping the hand in smoothing its rotation with the pen and enabling the calligrapher to unite between two parallel lines," explains Sayegh. "The inclination helps to brand ane side of the pen like a dot where the left and correct sides meet every fourth dimension the alphabetic character reaches its end or meets another letter. This design is ane of the secrets of the art of calligraphy and makes it a witness to the subconscious order of the universe."

Although the pens used past calligraphers evolved over time — particularly post-obit the development of scripts such as Diwani, Diwani Jali and Ruqʿah — they were essentially variations on the original qalam. "Information technology is interesting to note that this evolution was the outcome of the prevalence of the utilitarian side of calligraphy over its aesthetic side," adds Sayegh. "Pens that prioritized writing and conveying the linguistic content did not seek more inventiveness as much every bit they sought solutions that residue beauty and utility, such as the Naskh, Taliq and Ruqʿah scripts."

The aforementioned pens are still in employ today. Shawkat uses traditional styles such as the Khamish, Handam and Java, too as mod pens such as the Tomar, which is fabricated from a large slice of bamboo or forest. He as well uses Pilot Parallels that have been modified for the Arabic linguistic communication and different brands of fountain pen with modded nibs, such as Pelikan and Osmiroid. Sayegh, whose fine art is based on individual letters or words, has seen the pens he uses abound in size, nonetheless the essence of their design has been preserved.

The paper used today tends to be handmade in countries including Nepal, India and Nippon, but early on calligraphers wrote on parchment made of sheep or deer pare. Such parchment was used for writing letters, official documents and religious texts and continued to be produced until the 11th century. The inflow of paper from Cathay in the 8th century, however, led to the cosmos of the first paper factories in Samarkand and eventually to the product of paper in Baghdad, Damascus and Cairo.

Yet, newspaper posed two issues for calligraphers. Firstly, it was absorbent. Secondly, information technology tended to be rougher than parchment and was not smooth enough to allow the pen and the ink to flow well. These problems were overcome with the application of coatings, which gave the newspaper a glossier finish once dry. Such paper is oftentimes called Ahar, or Muqahar.

"For the calligrapher, paper has to abandon its own presence in guild to reveal calligraphy's full appearance," says Sayegh. "Paper in relation to calligraphy is similar a mirror in relation to the face — the cleaner and the more than neutral it is, the clearer the confront appears. Paper has to withdraw in order for calligraphy to fill up the place.

"We strive today to sympathize the meaning of absence, withdrawal, cleanliness, neutrality and clarity," he adds. "And according to our different agreement of the terms and our unlike intentions of use, materials that volition acquit the calligraphy will also change."

A student practices calligraphy using a traditional reed pen at the Dar Al-Qalam Complex in Saudi Arabia. (Arab News)

A student practices calligraphy using a traditional reed pen at the Dar Al-Qalam Complex in Kingdom of saudi arabia. (Arab News)

Reed pens combine hardness and softness, solidity and flexibility. (Shutterstock)

Reed pens combine hardness and softness, solidity and flexibility. (Shutterstock)

Turning the folio

Whatsoever word of calligraphy's function in the modernistic globe cannot be limited to calligraphy itself. It must encompass the entirety of its legacy, from art and typography to design and branding.

As Shamma says, calligraphy is the foundation of typography, which has had a profound impact on the evolution of graphic pattern. "This is apparent in the way typography has evolved every bit an art form in itself," she says. "You also see Standard arabic calligraphy transcending pen and paper in the form of calligraffiti, with artists such as eL Seed combining street art with calligraphy and covering building facades to highlight compages and often times unite communities around the messages depicted."

French-Tunisian artist eL Seed merges a variety of influences. Hither, he talks to us about his groundbreaking approach from his studio in Dubai.

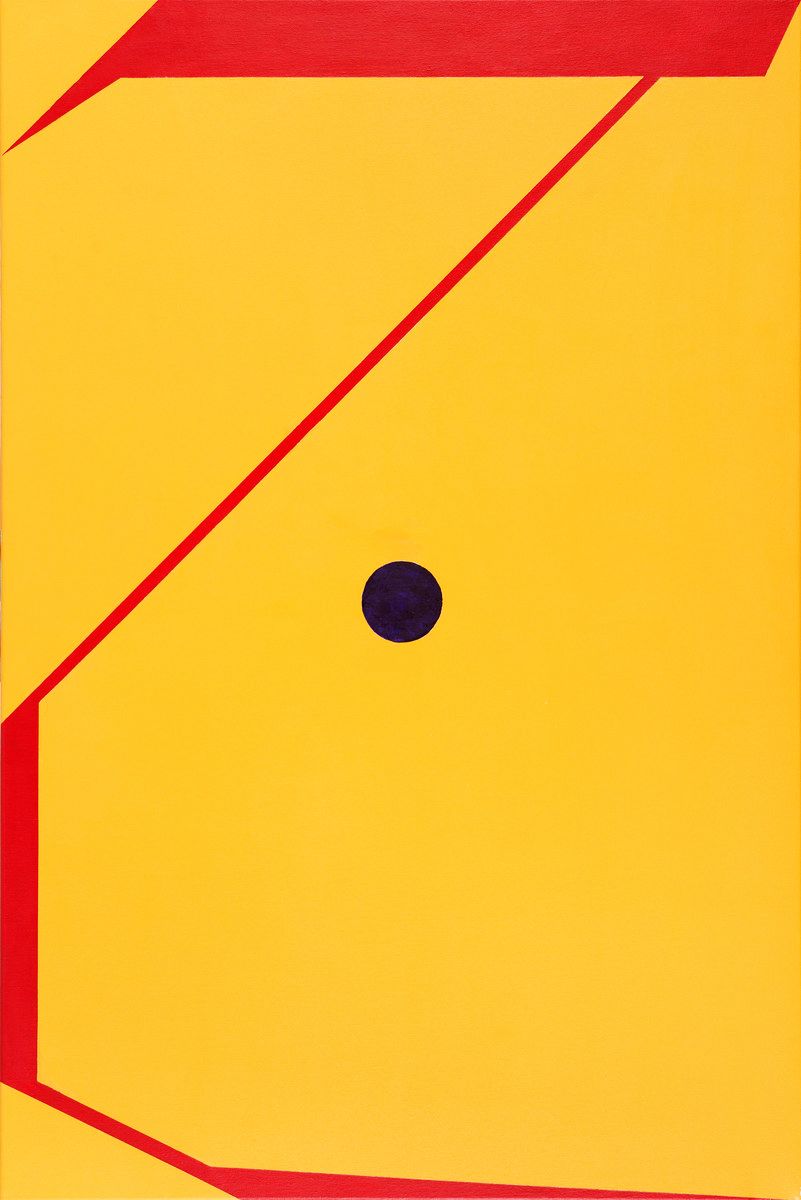

Another instance is the intricate work of Saudi creative person Lulwah Al-Homoud, who incorporates Arabic letters to create circuitous abstract works on newspaper, synthesizing characteristic motifs from Islam with the rhythms found in calligraphy and geometry to transform them into a new visual vocabulary, thereby breaking the mold in her ain way.

Built-in in 1967 in Riyadh, Al-Homoud now lives and works betwixt Dubai and London and seeks to contain calligraphy in her abstruse piece of work in a way that departs from the art form's original use. "The way I apply my compositions of messages and words is unconventional," she says. "The fashion I utilise calligraphy is non meant to be read. It volition inquire people to look more deeply into the painting to be able to figure out what is written. Information technology is not direct. In that location'southward a visual ambivalence to my work. I deconstruct the words in my piece of work and so rebuild them."

Saudi artist Lulwah Al-Homoud incorporates Arabic messages to create complex abstruse works and spoke to us most her creative procedure.

All the same the tendency toward a realignment around fine art and design, combined with the predominance of printing and the digitization of the Arabic script, has had a considerable impact on traditional calligraphy. In Egypt, a country still considered to be a calligraphic hub, institutes such as the Khalil Agha Schoolhouse are struggling to survive post-obit the removal of land funding, while calligraphy'southward popularity across the wider Arab world has declined. Both the Madrasat Tahsin Al-Khotoout in Cairo and the Medresetul Hattatin in Istanbul take long since airtight. In turn, the need for calligraphers has itself macerated. "It is said that in the 19th century at that place were around 1,500 calligraphers in Istanbul," says Massoudy. "And when the printing press was introduced they protested with a coffin that had their pens in it."

"The traditional practise of calligraphy has suffered from a turn down since the invention of the printing printing," adds Alyousef, who works in the fields of creative blueprint, typography and calligraphy. "As time goes by and applied science advances, the need for a calligrapher who writes books is extremely rare. But the rich heritage and aesthetic values of calligraphy make it very valuable in abstract art, compages, pattern and other similar fields. That's why I think the best way to keep and even accelerate the teaching of calligraphy comes through a deeper study of design, form and abstraction."

In Standard arabic typography, designers are creating groundbreaking work inspired by calligraphic forms to create fonts that reflect the world nosotros alive in. In doing so, they are finding "solutions to bug of legibility and aesthetics and creating fonts that are truly unique, proportionate and functional," says Basma Hamdy, an Egyptian designer, educator and the author of "Khatt: Egypt's Calligraphic Landscape."

In the realm of fine art, Sayegh has ignored the calligraphic rules established by Ibn Muqla, stylizing both the geometric and cursive variations of Arabic calligraphy to create a universally appreciable practise based on form and beauty. For his geometric work, that has meant a focus on equilibrium and a dialogue between line and space. For the more free-flowing pieces, it has meant a system based on move and remainder. He has full-bodied on freeing calligraphy from the constraints of language.

Massoudy, too, has taken individual letters, words and phrases and created vibrant works of art that, despite their suspension with tradition, continue to limited the dazzler of Arabic calligraphy. Both artists are considered to be function of the motion known as "Hurufiyya," which combines tradition with modernity to create a culturally specific visual language.

The desire to bring calligraphy into the mod historic period is echoed by Saudi artist Al-Salem, who "began questioning how I could make my calligraphy go a contemporary fine art form."

Al-Salem is known for his recontextualization of calligraphy in mixed-media formats. He uses neon tube lights, concrete blocks and laser-cut stainless steel to create new forms of calligraphy that defy convention.

"I began as a classical calligrapher," he explains. But having traveled abroad, he says he realized "I wanted it to co-exist within the realm of contemporary art. I was asking myself the question that about calligraphers today ask themselves: How can we evolve from such an ancient and traditional art form?"

Saudi artist Nasser Al-Salem speaks to united states about his approach to the art of the written word, particularly his dearest of mixed media formats.

In their own manner, street artists such as eL Seed and Yazan Halwani, who merge Standard arabic calligraphy with graffiti fine art, have besides helped to breath new and visually intriguing life into scripts such every bit Kufic, Diwani and Thuluth. Halwani in detail, with his focus on cultural icons and the writings of poets including Mahmoud Darwish, has contributed towards the Arabic script's continued role as an integral part of Arab and Islamic identity.

"As long as Arabic is a spoken language, Standard arabic text continues to be the visual language that accompanies information technology," says Art Jameel's Shamma. "The application of calligraphy in innovative ways using different media and conceptual research is evidence of its influence in current practices."

Shamma cites the Iraqi artist Mehdi Moutashar, who used Arabic script every bit the inspiration for his piece of work "Two Folds at 120 Degrees," and Shehab'due south "A Thou Times No," which featured 1,000 different versions of the word 'la.' The latter was showtime exhibited on a plexiglass curtain measuring iii.5m past 7m in 2010. Shehab also compiled her research into a book, which placed each depiction of the discussion 'la' chronologically, stating the place she had found it, the medium used, and the patron who had deputed the work. "I'm inspired by history to comment on the current situation," she says. "For me, calligraphy is a manifestation of identity."

Shehab has too founded Blazon Lab within AUC to document the varying forms of Standard arabic lettering. And then far the lab has documented almost lxx,000, with the goal of helping designers create solutions for the hereafter. "The future lies with the youth who are supposed to design a new Arab identity," she says. "In one case they understand their history they will be able to blueprint their hereafter."

Non everyone has embraced this dauntless new world. Many traditionalists believe that proportion and form in calligraphy should exist adhered to, not discarded with nonchalance. And while many believe there is room for modernization and the development of new scripts, others defend classical tradition. Others question whether movements such equally calligraffiti, which has no rules and requires no formal grooming, should even exist talked about in the aforementioned jiff equally calligraphy.

"I say to those who refuse to wait at new currents and new methods in Arabic calligraphy: If we had applied such an idea to calligraphy for the previous ane,000 years, we would still simply be using Kufic," says Massoudy. "What nosotros see today are the styles that have been created by innovators from every era. Perchance, in their time, these innovative new methods of calligraphy were met with similar doubts. Yet, these styles have become function of our history and have been placed in glass boxes and kept in condom places such equally museums, where we preserve them as we preserve everything that is morally and materially valuable. Therefore, every rejection of artistic or literary production is nil just a contribution to the impoverishment of society."

What we see today are the styles that have been created by innovators from every era.

None of which means traditional Standard arabic calligraphy is in terminal decline. Far from it, in fact. Spurred on by exhibitions, workshops, talks and prizes, peculiarly in the UAE and Saudi Arabia, it is once again being celebrated in all its forms. Nowhere more then than in the Saudi Ministry of Culture's Year of Standard arabic Calligraphy.

"There is a big place for calligraphy in our modern world. With ever-evolving technologies, I see a futurity world where calligraphy and the formal dazzler of the script go an of import, if not a necessary, component of our everyday experiences. I believe we adapt to what we are served or presented with," says Hamdy. "Why can't we imagine a earth where calligraphic beauty becomes a necessity for communication? Where wonder is embedded in the simplest acts of reading and deciphering?"

French-Tunisian artist eL Seed is part of a new wave of calligraphy-focused artists. He has created works across the globe, including 'Perception' in Cairo, pictured here. (Supplied)

French-Tunisian artist eL Seed is office of a new moving ridge of calligraphy-focused artists. He has created works across the world, including 'Perception' in Cairo, pictured here. (Supplied)

Lebanese artist Samir Sayegh has ignored the calligraphic rules established by Ibn Muqla, stylizing both the geometric and cursive variations of Arabic calligraphy. (Supplied)

Lebanese artist Samir Sayegh has ignored the calligraphic rules established by Ibn Muqla, stylizing both the geometric and cursive variations of Arabic calligraphy. (Supplied)

Hassan Massoudy has taken individual messages, words and phrases and created vibrant works of art. (Supplied)

Hassan Massoudy has taken individual letters, words and phrases and created vibrant works of art. (Supplied)

Credits

Editors: Saffiya Ansari, Mo Gannon

Creative director: Simon Khalil

Graphics: Douglas Okasaki

Designer: Omar Nashashibi

Video producer: Eugene Harnan

Video editors: Ali Noori, Farah Heiba

Blitheness: Wild Studio

Moving-picture show researcher: Sheila Mayo

Editorial researcher: Rebecca Anne Proctor

Copy editor: Adam Grundey

Social media: Mohammed Qenan Al-Ghamdi, Hams Saleh, Ane Carlo Diaz

Producer: Arkan Aladnani

Editor-in-chief: Faisal J. Abbas

Special thanks: Taha Al-Hiti

Source: https://www.arabnews.com/ArabicCalligraphy

0 Response to "The Fine Art of Handwriting Is the Chief Form of Islamic Art"

Postar um comentário